002 Natural History Museum, Locarno

Type of mandate: Competition

Client: Canton Ticino

Study period: 2022

Budget: 33’500’000 CHF

Built area: approx. 3’000 m2

Project area: approx. 12’000 m2

Program: Cantonal Museum of Natural History, Offices,

Library, Archives and Cafeteria

Lead Architect: sub, Berlin

Andrea Faraguna, Iwona Boguslawska, Roula Assaf, Patricia Bondesson Kavanagh, Deniz Celtek, Kate Chen, Marc Elsner, Martin Raub

Executive Architect: Djurdjevic Architects, Zürich

Muriz Djurdjevic

Landscaping: Forster-Paysage, Lausanne

Jan Forster, Ludovic Heimo

Context

Nestled in the Alpine foothills, the Swiss town of Locarno is known for being a picturesque and warm-weathered holiday destination, as well as a peaceful home to those who live there. But the geography of this region, rich in botanical wonder and political history, belies a dramatic geological history, eons older than any human.

Locarno is built along the shoreline of the glacial-tectonic Lake Maggiore, marking Switzerland’s lowest point of elevation, and only a few mountain peaks away from the Periadriatic seam, the geological fault where once the Adriatic and European continental plates collided. In the surrounding mountains, there are vast folds of sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous rock, where once stones from the bowels of the Earth were pushed up into the heavens. The great seismic movement of these plates continues into the present, with their ongoing collision producing a volcano zone in Southern Europe.

In our proposal we fully embrace the locality of Locarno and the materiality upon which it is built, as means for inviting visitors to a spectacular story that winds through time itself. Our design provides not only a versatile and engaging museum experience, but a new meeting ground within the city where we can together celebrate the wonder of our both fragile and resilient planet.

Concept and Urban Intervention

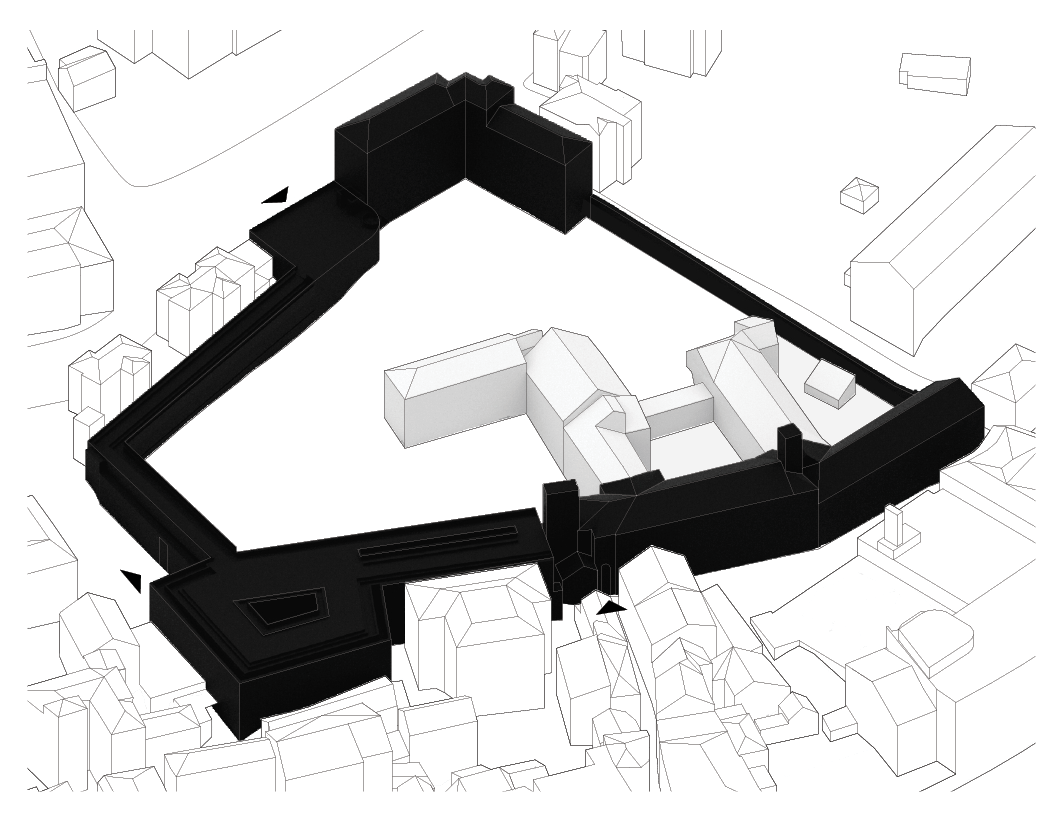

Our concept for the Cantonal Natural History Museum is founded on a deep reading of the original site. With the original architecture of Santa Caterina Monastery in mind, our aim is to build on this foundational history, much like strata accumulate history into the Earth. In our studies we identified two striking signa. The first was the presence of a medieval stone wall. Erected with local stone, this feature protected the second signum, a peaceful monastic garden cultivated by the Augustinian Nuns to grow vegetables. For the proposal of the new complex, the ancient stone wall and the hortus conclusus, or enclosed garden, have acted as shepherds in guiding the final design.

The materiality of the stones and mortar of the wall extend to the structure at large, imagining the building as an inhabited wall. As the original, it protects a sacred greenery within it in the form of the museum garden. The hortus conclusus is a recognizable emblem of High Medieval Europe, also figuring popularly in later Renaissance poetry and art. Beyond allegory, a practical function of enclosed gardens is the rendering of a stable microclimate therein. In our design the decision to make this a central feature of the museum relates directly to Locarno and the adjacent Lake Maggiore, which are walled to the North by the Southern Swiss Alps, imbuing it with an unusually temperate climate and a unique biome hospitable to Mediterranean, tropical flora and desert flora.

The top of the inhabted wall, accessiblke to the public, also serves as connecting path between via Cappuccini and Via Santa Caterina. Rather than an urban intervention, our aim was to conceive of an urban dialogue between past and future. To do so we engaged with the architectural emblems of the original site, foregrounding the symbolic legacy of walls and load bearers of history and archeological signposts of past civilisations. Upon this wall the public can take in views of the Locarno panorama as well as the enclosed garden below. In classical hortus conclusus it was traditional to include an allegorical fountain of life at the heart of the garden. In the proposal for this new museum complex the garden becomes symbolically the fountain, representing the hopefulness and resilience of life on our planet in the form of a wild and legally protected garden.

The Garden

For the Santa Caterina Monastery, the monastic garden would have provided a cornucopia of vegetables and herbs, as well as a space for meditation. The new proposed garden design seeks to meditate on the plants themselves, and return to them a site for rewilding and unbounded growth. It collapses the notion of a Natural History Museum as the site of artifact and fossil instead seeking to underscore that the plants that live today have an agency and lineage which reaches back some 500 million years. In the spirit of the Anthropocene and an expanded understanding of ecology, the story of human beings as custodians of nature is deeply anthropocentric. In deep time, our story is only a small part in the life of plants, for without their ability to transform solar energy into biomass this would be an oxygen-less and barren world.

Inevitably entangled with the culture that sows them, gardens come to represent the shifting tides of how humankind has conceptualized the natural world. Whether ornamental or purposed for horticulture, mystically Edenic or peacefully Zen, gardens reflect as well as contrast changing beliefs on what constitutes nature. These attitudes have taken many forms, from the Sublime wilderness of the English landscape garden to the paradiscial Persian and geometrical formal French, among countless others. As we have gained more complex understandings of the ecosystems that enmesh our lithosphere and with the rise of Environmentalism during the 20th century, gardens have been re-thought as sites of conservation and rewilding, incorporating notions of soil rehabilitation and habitat protection and production.

The new garden of the Cantonal Natural History Museum acknowledges these histories, both human and non-human, and seeks to symbolically release the plants therein from the grip of anthropogenic control. Imagined both as subversive and sacral, the garden will bring together vegetal species from the Carboniferous era and onwards, creating a landscape of tree ferns, horsetails and sago cycads, as well as Cretaceous conifers, magnolias and many others, allowing these to grow unhindered in perpetuity. It speculates on a deep future where, as vines upon the ruins of a stone wall, the garden might one day subsume the museum. It invites the visitor not to a utopia but to a truly radical act of rewilding, which imagines life on this planet not as a line but as a constantly evolving dimension. The selection of species and planting layout will be developed with Locarno’s unique microclimate in mind, in order to honor the rich botanical garden culture of the region.

The garden is not accessible to human beings, it is land returned to nature, a place of re- enchantment, to acknowledge and respect the ineffability of existence.

Architectural Principle

Beyond playing with the typology of the monastery in the form of the closed garden and the expanding wall, the new building also integrates the classic geological notion of vertical strata. It imagines history as soil horizons, and figuratively as well as literally burrows down into the Earth. Each floor of the museum represents a separate thematic approach to expanses of time, from the geological - to the archeological - to the historical.

A low incline slope connects through each level, rolling up and around a narrow, long light well. This enlongated well creates a link from the sky above into a deep crevice in the ground below, allowing rainwater to percolate and sunlight to streak through. This open feature concludes on the lowest level with an inverted sculpture feature in the form of a chasm, reminiscent of geological fault lines and tectonic rifts. The light well ties together the separate histories of the museum, allowing the visitor when standing on the roof to gaze down both figuratively and literally, through the layers of deep time.

Museological Vision

The museological vision is based on this notion of a spatial and temporal descent and ascent. This would begin with the visitor descending to the lowest level, closest to the mantle of the Earth. This level most deeply explores deep time and geological history–a world of minerals in constant flux, with vast tectonic plates coming together and creating new lands, exploring the fossil remnants of local megafauna and dinosaurs, and the many paleoclimates our planet has experienced. While ascending the visitor arrives in a nearer history, the history of the Hominid, and the glacial shifts our developing species have faced. Arriving on the third level the visitor explores the emergence of agriculture and industry as a precursor to the development of the Anthropocene as a school of thought. The present day and by extension the future is accessed on the roof. The overgrown garden, as well as the cityscape, is an integral part of this viewing experience and meant to elucidate the past not as a lost place, but as a mutable and constantly evolving idea, closely entangled with the now.

Materials and Durability

The materials utilized for the construction of the building are chosen on two bases. The first is their correlation to the original stone wall, as a means of materially re-interpreting it. The second is based on principles of sustainability and repurposing, utilizing waste products of local industries as well as quarry by-products. Perimeter retaining structures will be integrated by means of traditional techniques in order to create an architecture that expresses the weight of medieval structures while minimizing environmental impact.

The outer faces of the new building are extensions of the existing wall perimeter, fabricated by mixing cementitious binders with debris produced by the demolition of disused buildings. The interior walls of the building will be clad using different materials that will characterize each level, evoking the evolution of the built space from prehistory to the present time.

Each of the three main levels of the exhibition galleries will express a specific material character. The lowest level will have a cavernous character, ideally carved into the natural substrate, using discarded stone blocks from local old quarries; the walls of the level dedicated to archaeological time will be made of compressed earth and aggregates mixed with trass lime; the level dedicated to historical time will be covered with recycled bricks. The walls of the two upper floors, representing present time, will be made with concrete mixed with plastic waste.

Type of mandate: Competition

Client: Canton Ticino

Study period: 2022

Budget: 33’500’000 CHF

Built area: approx. 3’000 m2

Project area: approx. 12’000 m2

Program: Cantonal Museum of Natural History, Offices,

Library, Archives and Cafeteria

Lead Architect: sub, Berlin

Andrea Faraguna, Iwona Boguslawska, Roula Assaf, Patricia Bondesson Kavanagh, Deniz Celtek, Kate Chen, Marc Elsner, Martin Raub

Executive Architect: Djurdjevic Architects, Zürich

Muriz Djurdjevic

Landscaping: Forster-Paysage, Lausanne

Jan Forster, Ludovic Heimo

Context

Nestled in the Alpine foothills, the Swiss town of Locarno is known for being a picturesque and warm-weathered holiday destination, as well as a peaceful home to those who live there. But the geography of this region, rich in botanical wonder and political history, belies a dramatic geological history, eons older than any human.

Locarno is built along the shoreline of the glacial-tectonic Lake Maggiore, marking Switzerland’s lowest point of elevation, and only a few mountain peaks away from the Periadriatic seam, the geological fault where once the Adriatic and European continental plates collided. In the surrounding mountains, there are vast folds of sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous rock, where once stones from the bowels of the Earth were pushed up into the heavens. The great seismic movement of these plates continues into the present, with their ongoing collision producing a volcano zone in Southern Europe.

In our proposal we fully embrace the locality of Locarno and the materiality upon which it is built, as means for inviting visitors to a spectacular story that winds through time itself. Our design provides not only a versatile and engaging museum experience, but a new meeting ground within the city where we can together celebrate the wonder of our both fragile and resilient planet.

Concept and Urban Intervention

Our concept for the Cantonal Natural History Museum is founded on a deep reading of the original site. With the original architecture of Santa Caterina Monastery in mind, our aim is to build on this foundational history, much like strata accumulate history into the Earth. In our studies we identified two striking signa. The first was the presence of a medieval stone wall. Erected with local stone, this feature protected the second signum, a peaceful monastic garden cultivated by the Augustinian Nuns to grow vegetables. For the proposal of the new complex, the ancient stone wall and the hortus conclusus, or enclosed garden, have acted as shepherds in guiding the final design.

The materiality of the stones and mortar of the wall extend to the structure at large, imagining the building as an inhabited wall. As the original, it protects a sacred greenery within it in the form of the museum garden. The hortus conclusus is a recognizable emblem of High Medieval Europe, also figuring popularly in later Renaissance poetry and art. Beyond allegory, a practical function of enclosed gardens is the rendering of a stable microclimate therein. In our design the decision to make this a central feature of the museum relates directly to Locarno and the adjacent Lake Maggiore, which are walled to the North by the Southern Swiss Alps, imbuing it with an unusually temperate climate and a unique biome hospitable to Mediterranean, tropical flora and desert flora.

The top of the inhabted wall, accessiblke to the public, also serves as connecting path between via Cappuccini and Via Santa Caterina. Rather than an urban intervention, our aim was to conceive of an urban dialogue between past and future. To do so we engaged with the architectural emblems of the original site, foregrounding the symbolic legacy of walls and load bearers of history and archeological signposts of past civilisations. Upon this wall the public can take in views of the Locarno panorama as well as the enclosed garden below. In classical hortus conclusus it was traditional to include an allegorical fountain of life at the heart of the garden. In the proposal for this new museum complex the garden becomes symbolically the fountain, representing the hopefulness and resilience of life on our planet in the form of a wild and legally protected garden.

The Garden

For the Santa Caterina Monastery, the monastic garden would have provided a cornucopia of vegetables and herbs, as well as a space for meditation. The new proposed garden design seeks to meditate on the plants themselves, and return to them a site for rewilding and unbounded growth. It collapses the notion of a Natural History Museum as the site of artifact and fossil instead seeking to underscore that the plants that live today have an agency and lineage which reaches back some 500 million years. In the spirit of the Anthropocene and an expanded understanding of ecology, the story of human beings as custodians of nature is deeply anthropocentric. In deep time, our story is only a small part in the life of plants, for without their ability to transform solar energy into biomass this would be an oxygen-less and barren world.

Inevitably entangled with the culture that sows them, gardens come to represent the shifting tides of how humankind has conceptualized the natural world. Whether ornamental or purposed for horticulture, mystically Edenic or peacefully Zen, gardens reflect as well as contrast changing beliefs on what constitutes nature. These attitudes have taken many forms, from the Sublime wilderness of the English landscape garden to the paradiscial Persian and geometrical formal French, among countless others. As we have gained more complex understandings of the ecosystems that enmesh our lithosphere and with the rise of Environmentalism during the 20th century, gardens have been re-thought as sites of conservation and rewilding, incorporating notions of soil rehabilitation and habitat protection and production.

The new garden of the Cantonal Natural History Museum acknowledges these histories, both human and non-human, and seeks to symbolically release the plants therein from the grip of anthropogenic control. Imagined both as subversive and sacral, the garden will bring together vegetal species from the Carboniferous era and onwards, creating a landscape of tree ferns, horsetails and sago cycads, as well as Cretaceous conifers, magnolias and many others, allowing these to grow unhindered in perpetuity. It speculates on a deep future where, as vines upon the ruins of a stone wall, the garden might one day subsume the museum. It invites the visitor not to a utopia but to a truly radical act of rewilding, which imagines life on this planet not as a line but as a constantly evolving dimension. The selection of species and planting layout will be developed with Locarno’s unique microclimate in mind, in order to honor the rich botanical garden culture of the region.

The garden is not accessible to human beings, it is land returned to nature, a place of re- enchantment, to acknowledge and respect the ineffability of existence.

Architectural Principle

Beyond playing with the typology of the monastery in the form of the closed garden and the expanding wall, the new building also integrates the classic geological notion of vertical strata. It imagines history as soil horizons, and figuratively as well as literally burrows down into the Earth. Each floor of the museum represents a separate thematic approach to expanses of time, from the geological - to the archeological - to the historical.

A low incline slope connects through each level, rolling up and around a narrow, long light well. This enlongated well creates a link from the sky above into a deep crevice in the ground below, allowing rainwater to percolate and sunlight to streak through. This open feature concludes on the lowest level with an inverted sculpture feature in the form of a chasm, reminiscent of geological fault lines and tectonic rifts. The light well ties together the separate histories of the museum, allowing the visitor when standing on the roof to gaze down both figuratively and literally, through the layers of deep time.

Museological Vision

The museological vision is based on this notion of a spatial and temporal descent and ascent. This would begin with the visitor descending to the lowest level, closest to the mantle of the Earth. This level most deeply explores deep time and geological history–a world of minerals in constant flux, with vast tectonic plates coming together and creating new lands, exploring the fossil remnants of local megafauna and dinosaurs, and the many paleoclimates our planet has experienced. While ascending the visitor arrives in a nearer history, the history of the Hominid, and the glacial shifts our developing species have faced. Arriving on the third level the visitor explores the emergence of agriculture and industry as a precursor to the development of the Anthropocene as a school of thought. The present day and by extension the future is accessed on the roof. The overgrown garden, as well as the cityscape, is an integral part of this viewing experience and meant to elucidate the past not as a lost place, but as a mutable and constantly evolving idea, closely entangled with the now.

Materials and Durability

The materials utilized for the construction of the building are chosen on two bases. The first is their correlation to the original stone wall, as a means of materially re-interpreting it. The second is based on principles of sustainability and repurposing, utilizing waste products of local industries as well as quarry by-products. Perimeter retaining structures will be integrated by means of traditional techniques in order to create an architecture that expresses the weight of medieval structures while minimizing environmental impact.

The outer faces of the new building are extensions of the existing wall perimeter, fabricated by mixing cementitious binders with debris produced by the demolition of disused buildings. The interior walls of the building will be clad using different materials that will characterize each level, evoking the evolution of the built space from prehistory to the present time.

Each of the three main levels of the exhibition galleries will express a specific material character. The lowest level will have a cavernous character, ideally carved into the natural substrate, using discarded stone blocks from local old quarries; the walls of the level dedicated to archaeological time will be made of compressed earth and aggregates mixed with trass lime; the level dedicated to historical time will be covered with recycled bricks. The walls of the two upper floors, representing present time, will be made with concrete mixed with plastic waste.